Presentation: Cybersecurity Training: Scaling CIA Methodology with AI

About Cyber Week

U.S. CyberWeek is a weeklong annual cyber festival hosted by CyberScoop October 19-23, 2020. This year U.S. CyberWeek was a digital experience featuring hundreds of national community events engaging the tens of thousands of people from the cybersecurity community and C-suite leaders from tech, gov and academia who came together to exchange information, share best practices and discuss the many ways we can revolutionize the way we protect against and overcome cyberthreats facing our nation.

Watch It Here:

Or Read It Here:

Let me begin with a question: Have you ever been in a training situation where you thought, “I know this already…do we really have to sit through an hour of this? I could teach this class.” Or how about the opposite, realizing with growing alarm, “I don’t have the foggiest idea what this guy is talking about…I think I signed up for the wrong session!” And finally, what about the computer based training scenario, which is more like, “I’ve got an inbox that’s piled high, multiple deliverables, and this now mandatory training, I’m going to brush through this as fast as I can so that HR can check the training box and my manager will get off my back about my not having taken the training.”

I’ve been in all these situations and they’re painful and unnecessary.

A different approach to training is needed, one that needs to involve the whole person in the context of their work. It needs to assess their existing knowledge, and it needs to draw them into what I call the adventure of knowledge discovery. This is true for any knowledge exchange, from training and education, to briefings and lectures, and even exchanges among friends and colleagues.

Here’s a story about what I mean, and when it was told to me it wasn’t a pleasant exchange. It took place in Santa Monica a while back when I and the management team at what is today GoSecure were practicing our pitch for a potential investor in front of the chairman of the board, Admiral William Fallon, a retired US Navy admiral and war-time commander of the US military’s Central Command. At the end of our team pitch, he jumped to his feet with irritation and declared that we needed to take a page from President George W Bush’s briefing style who Fallon had watched scold briefers saying two words, “Faster! Funnier!”

Believe me, it took me a while before I could appreciate Bush’s demand. But it gets right back to what makes knowledge memorable, and information relevant and sticky. “Faster, funnier” was Bush’s way of saying, “Listen, I’m not connecting. This doesn’t seem relevant. It’s in one ear out the other. Can you just get to the point? I want to know what’s important for me."

Here’s the problem: there are some huge challenges when it comes to delivering “faster, funnier” cybersecurity training for the entire enterprise, from new interns to executives in the C-suite.

Here are four problematics that cybersecurity training must contend with:

- Numbers: Every person across the enterprise needs training. No one is exempt, though some people need it more than others. And the educational process never stops, because the threatscape is constantly evolving and so the education must continue.

- Subject Matter: This is complex stuff. The technology that’s being exploited or weaponized in the broad world of cyberspace is not easy to understand, and really only understood by subject matter experts, the wizards.

- Relevance: The value proposition for training is not really understood by a lot of people. At least, it’s not particularly compelling, until it’s too late. That was a huge problem at CIA, since officers would push back saying, “We’re involved in operations, we don’t have time for training!” I’ve seen it in the commercial world too, people are already busy enough and stressed with the work they have, and training in a domain that is not their area of specialization can seem irrelevant.

- Psychology: This is the biggest challenge I have. Building security awareness in terms of threats and vulnerabilities is not appreciated at the psychological level by most. And by “appreciated,” I mean viewing cyberspace as including a combat zone, with an entire ecosystem of very nasty and malicious characters operating alongside the good guys. When I train folks, I challenge them to try to bring to mind the face of a hacker. You can do it for sports stars, Hollywood personalities, and politicians, but they can’t put a face to these threat actors. If they can’t imagine the threat, it’s challenging to grasp it at the psychological level.

As a trainer and security coach at Intellectmap, I needed a methodology that would allow me and my team to face these challenges effectively and have the potential to generate strong learning outcomes for my clients, whether they have 60 or 6000 employees. This is where my 15 years with the US Central Intelligence Agency’s Directorate of Operations come into play, both in the Information Operations Center and the Counterintelligence Center, fighting the bad guys.

The essence of human intelligence collection is being able to find the right people at the right time to provide high-value information to US government decision makers. Acquiring sources (or “assets” as we called them) requires a highly refined, repeatable, tested and proven method, which is known as the Recruitment Cycle.

That approach to recruiting “assets” – we never used the word spies – was ingrained in young trainees throughout the course of the most intensive and lengthy training offered by any US Government agency that is known as operational certification training, and then applied continually through headquarters desk assignments and foreign field assignments.

I want to walk you through this cycle and share with you:

- Why I think it’s so relevant to the cybersecurity training that I do,

- How the cycle can be transformed into a new way of building security awareness, and

- How it’s one big weakness can be overcome.

The recruitment cycle is described by a simple acronym: SADR. Spotting, Assessing, Developing and Recruiting

Spotting

Spotting is pretty basic. In the spy world, everything we do is trying to identify a potential source who can provide access to high-value intelligence for US national security – this is such an important function that the CIA even created an entire job category of “targeting officers” who are known as “the hunters and detectives of CIA…They are the targeters who identify the people, relationships, and organizations that the Agency needs to focus on.” I’m proud to say that I played a small role in encouraging the creation of this career path.

Assessing

From spotting we go to assessing. That’s where the individual that we’ve spotted is looked at to see if they have the personality, character, access and trustworthiness to be a source. At CIA that can involve the work of many different kinds of officers, from targeters to counterintelligence officers, from psychologists to scientists, and of course the front-line case officers. I once even used for assessing somebody the services of a graphologist (handwriting analyst) and their insights were astounding and very helpful.

Developing

Developing is the art of bringing a person to trust in you, to want to help you, to come to believe in a cause, and to prepare them psychologically, materially or morally to accept to work with you usually at a significant risk to themselves.

Recruiting

And finally, there’s recruitment, where all that prep work comes down to getting the individual to really accept working for you. The recruitment pitch could involve months and months of work. It can be very discrete, it can leverage everything else that I mentioned, it can leverage signals intelligence collected by the NSA computer hackers, it can use allies’ intelligence services’ reporting, open source research, and deep ongoing reflection and judgment on the part of the recruiting officer. But it all comes down to, “I have to make a pitch! and the target has to believe me.”

Sometimes recruitment pitches are very soft, and CIA’s hand remains hidden, other times the risk is huge, and the CIA’s involvement must be made clear and obvious. Needless to say, the recruitment cycle is used by every other capable and effective intelligence agency in the world because it works.

1. Applying the Recruitment Cycle to Cybersecurity Training

How does the recruitment cycle apply to cybersecurity training today? To answer that, we need first to see where we are today with training. Currently, the cybersecurity training industry has essentially a one-size-fits-all approach. Of course, there are many flavors and colors of training options, from huge libraries of phishing templates to animated videos that are quick views, to short quizzes to colorful dashboards. But here’s the issue: the training industry has commoditized its service and its products, where the products are more and more similar and the decision to acquire the service essentially comes down to who is the cheapest. Or as the Gartner 2019 computer-based security awareness training magic quadrant report noted, “The current pricing environment feels like a race to the bottom.”

The “one-size-fits-all approach” is the opposite of the personalized approach. But though the personalized approach is just fine if my client is the COO of a company, or a handful of individuals, is it feasible for an entire company?

When I joined Intellectmap last summer, Ronan Sorensen the CEO and founder, and a friend of mine, challenged me with a question about cybersecurity training and how my background would fit into his vision of a different way of doing training. The question was as simple as it was overwhelming: How do you find inside a company the weakest human links in the complex security chain? Who are the persons most in need of training and in what areas of security awareness do they need particular help?

My initial response was that I needed to spend time inside the company, meeting all kinds of people, talking to them, asking them questions, probing their knowledge, holding small training sessions, assessing the company’s security posture, learning about what information and data the company considered high-value, who had access to that data and on what networks and devices.

“That sounds great,” Ronan said, “but there’s an obvious problem: time and scale. We’re not the CIA that can take months to assess an individual. And worse, your approach doesn’t scale rapidly across a lot of clients.” Here’s where Ronan brought me into what he’d been developing over the last 15 years at Intellectmap, and finally the light went off in my head.

2. Transforming the Recruitment Cycle with AI

There is a rapid and effective way to assess a large number of people’s security awareness using machine learning and artificial intelligence.

I know AI is a vast domain and today everyone is talking about it, but long before AI was a buzzword, Ronan was exploring how machine learning could map an individual’s thought processes. Ronan had even received a patent in 2010 for developing this “Method and System of Organizing Information Based on Human Thought Processes”. Applying this use of AI to cybersecurity training was a logical next step. He had the engine, and now he needed the content that the engine could deliver and the coach who had the credibility to work with the weak links the AI engine would spot. That’s where I and my background came in. Now it became possible to scale across the enterprise, with my knowledge and experience of the CIA’s recruitment cycle. This was a real thrilling discovery for me, not the least of which was the pleasure it gave me that we could do it in a very effective way and that we were real innovators, as no one else in the industry was doing this.

So, here’s how it works.

First, we needed to target everyone in the company from the CEO to the newest hire to assess their existing level of knowledge across the whole spectrum of cybersecurity awareness. We could do this with an AI-powered written assessment of a set of questions that I developed. This assessment also collected information about the individual’s position and access to proprietary information, which allowed us to add a risk weight to their assessment score based on how they self-identified.

Within a very short time, I am able to go into a client and assess the existing knowledge and awareness of its entire staff. I can quickly spot who is the weakest link in the security chain across multiple domains of cybersecurity – not just the usual ones of email and malware, but also information classification, the dark web and hackers, and incident response.

Now the relevance of the CIA’s recruitment cycle was energized and able to be scaled.

After the assessment, it was time to “develop” new knowledge and awareness. I develop my clients first through some traditional methods, such as engaging videos involving subject matter experts talking about these domains, but then we add an AI twist. After they watch the videos and absorb that learning from videos that I’ve curated – always asking whether this is really going to hit learners, including those who may come into it just wanting to get the training over with – they engage with our AI. And during the entire process, they are being assessed by the AI. It looks at their thought process and serves up questions based on their previous answers. Ultimately, no two staffers or learners are going to have the same results in the particular learning domain that they’re engaging.

It was a fascinating process for me to develop the content for the quizzes and then see how this content was digested by Ronan’s AI algorithms into a personalized quiz that assessed in real time how the learner was performing. For example, I’m able to identify how long somebody is spending on the answers to the quizzes, their dwell time, which tells me a lot about how they’re approaching the training; are they just clicking through? Are they taking this seriously?

This is where I as a coach can come in. I’ve now identified the weakest links, those who are struggling, those who need more engagement. I can send them an email; I can have a phone call and I can follow-up with them. I can have a human contact. It’s not just a machine that they’re engaged with. I can share additional knowledge. I able to motivate them. Some of them at the end of our conversation say, “I want to take that module over again!” That’s really cool.

And at the end of the training cycle, over the course of several months, and across 13 domains of cybersecurity, we then take the learner back to the same AI powered, assessment – this time they see the answers, and the AI engine shows the hopefully positive delta change in their awareness.

Developing a learner’s knowledge about cybersecurity means also moving them to the R in SADR – Recruiting.

Ultimately, I want to recruit the learner to take seriously in both their work and personal life, the realities of cyber threats, and to value their role as a link in the security chain, that is continually tested for its weak points by a very hostile ecosystem of malicious actors.

I believe that even a short 5 minute phone call, or a friendly email to specific individuals leveraging the knowledge that I gained from the AI assessment and quiz engines can play a critical role in moving training from a box checking exercise to a potential adventure in learning. I’ve seen this happen many times, where a learner is really appreciative for that contact, that reach out, because they know me from the very start of the training, and they also feel comfortable to push back or ask probing questions about the topics.

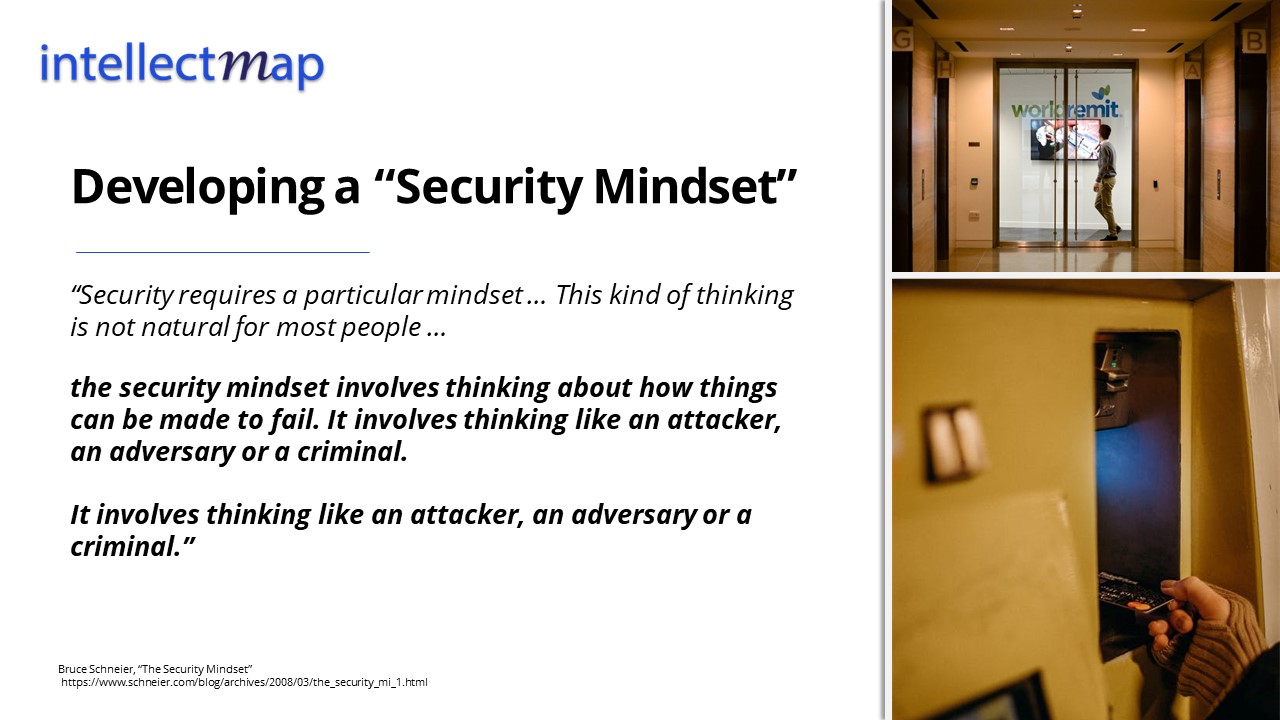

My ultimate goal in this training is to develop a new security mindset on the part of my clients. Some of you are probably familiar with Bruce Schneier’s work on the subject. He’s done more than anyone to explain why having a security mindset is so important. I used to share his books with other CIA officers and with officers at other allied intelligence agencies. He gets it. This is a mindset that can be developed, it means learning how to think about how things can be made to fail, how they can be exploited.

In my training I often share with my learners a couple of photos: one is of double glass doors and an ATM machine. With a security mindset I look at those doors in a different way. This was introduced to me when I was doing business consulting and a friend of mine returning from lunch said, “Hey, would you like to open the doors without your card key? I said, “How are you going to do that?” He said, “I’ll use the cardboard key!” And he went into the nearby trash room and grabbed a piece of cardboard, slipped it through the gap between the two doors, waved it around to trigger the inside motion detector and boom, the doors were unlocked! I was telling that to one of my learners who is a senior executive and he interrupted me and said, “I know that trick too! I’ve used it before.” That’s someone who has a security mindset.

Another example of the security mindset is how I look at ATM machines and I think about how they can be broken into. Is there a way to attach a card skimmer to the machine? These are just two examples of how security mindsets can be grown if you expose that person to this way of looking at things.

3. Overcoming the Challenge of the Non-Learner

One thing that I learned at CIA is that recruitments don’t always work, no matter how much of an effort was spent on the recruitment cycle. There will always be persons who turn it down, who walk away, and who don’t want to take the risk.

The same is true with learning new information. In fact, the CIA leadership development and leadership academy showed that between 15-20 percent of officers don’t want to learn; they’ve already got the answers so there’s nothing to learn. They’re the ones who sit in training classes with their arms crossed and roll their eyes, are disengaged and “have got better things to do”.

Cybersecurity training and the SADR methodology allows me to spot the non-learners pretty quickly. Whether it’s running through the assessment in an unreasonable time or even refusing to take the assessment, clicking through the quiz answers in 2 seconds, tone of voice on the phone during a personal coaching call, it’s pretty evident to me.

There’s also the problem of workplace culture and business models that reduce security to a cost center, a specialized area for experts to busy themselves, a culture that sees security as a drag on the real business of the company.

I actually had this challenge with a good friend who works for a global organization where he is a senior security executive. We were talking about Intellectmap and what we do with our AI-powered cybersecurity training, he responded that “We’re too busy, our executives don’t have time for this training. I’ve seen it again and again, with our own in-house security training. They’re not going to take it. What do they need to know about all these details? We already have a password manager, what do they need to know about password cracking.”

You know what it boiled down to and what he was really telling me? That this is an organization that doesn’t value security, and that’s like the recruitment turndown, because there are some places where it’s going to be really hard to embed cybersecurity learning at the leadership level.

Which brings me to a vital insight that I’ve gained across my career, from CIA to Corporate Security and Business Continuity at Deutsche Bank on Wall Street, to pitching end point real time threat detection for NeuralIQ (today GoSecure) to US Government prospects, to homeland security consulting and engaging police chiefs from across the USA, to hunting the hidden assets of some of the world's most violent kleptocrats for George Clooney’s NGO – again and again and again I’ve seen that the organizations that have the best security awareness are those where security awareness was part of the leadership culture, where real risk leadership was recognized and rewarded, where the C-suite walked the walk and talked the talk, and put actual skin in the game.

Here are a few examples that I’ve seen of what risk leadership looks like.

- A station chief whose team foiled a major terrorist attack in Asia and instead of the normal response of high-fives and self-congratulations, he convened his team to spend all afternoon reviewing where things could have gone wrong, where they really just got lucky, and what were the lessons learned.

- A major US corporation that probably employs more people than any other company, that invited a former boss of mine from the Information Operations Center for a two-day security seminar with all the executive leadership.

- An IT security company that turned an unfortunately successful pen test that showed critical network vulnerabilities into an action video with music and different camera angles, taking what is a pretty boring topic and making it exciting, and then showed it at a board meeting to stress how they were improving security.

- At Deutshe Bank, despite all its known public failings, we did things that very few other banks were doing as effectively at the time, like systematic crisis management exercises that would convene all kinds of individuals form back office personnel, bankers, regulators, FBI, NY Police Department. We’d get in the room and run through table-top exercises that would have people sweating it out in places like Singapore, Mumbai, New York City, London and Frankfurt, building that resiliency and security psychology. When I was head of the Red Team at Deutsche Bank, we proactively modelled threats to the bank’s people, processes and infrastructures.

My point here is that you can have the best security training methods, and very unique ones like we have at Intellectmap, but I also need to have an engagement by the leadership. I've been fortunate that a number of my clients have that mindset at the highest levels to do training and do it well. They’re willing to engage the AI powered training that allows us to spot, develop, assess and recruit learners, but also to engage me as a coach, as someone who will reach out to those who have the most need.

Look, I've talked enough so feel free to ask any questions, jump in, share stories of your own, push back. I'm all ears. Thanks a lot.

Watch the video to hear the full Q&A

Mark served 15 years in the CIA's Directorate of Operations including providing oversight of black hat info ops as well as leading investigations of threats to US critical infrastructures. On Wall Street, Mark led the Red Team program for one of the world's largest multinational banks, proactively modeling threats to the bank's people, processes, and infrastructures, and subsequently joined the management team of what is today GoSecure. As a homeland security consultant for National Strategies, he advised corporations and police executives on cybersecurity best practices. He presently serves as Practice Lead for Intellecmap's Intellect Security solution.

Back to Resources

|

|